Please wait...

About This Project

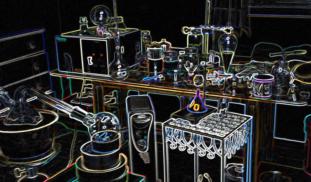

This is the first part of a multi-phase experiment in which I will prove that substances isolated from plant fermentation can be used to allay toxic corrosives and heavy metals, thereby transforming them into bio-available substances which support organic growth.

In this first phase, I will illustrate a new chemical process to render insoluble metallic salts, soluble, creating a new type of corrosive which will be used in the next phase.

Browse Other Projects on Experiment

Related Projects

From Minerals to Medicines: A New Technology for Heavy Metal Pollution Remediation

This is the first part of a multi-phase experiment in which I will prove that substances isolated from plant...