About This Project

If doctors think infants will have lower skill (e.g., less able to look and to smile at parents), does that bias lead them to expect mental health problems for the infants and their parents? We want to know! We think doctors’ mindsets about a baby’s potential to do things can affect how parents feel about themselves and their baby. This idea is important to study since positive views of one’s infant with a disability are linked to better attachment and to mental health benefits for parents.

Ask the Scientists

Join The DiscussionWhat is the context of this research?

Parents see doctors as experts. If doctors expect poor outcomes for infants with certain diagnoses their lack of enthusiasm may lead to the results they tell parents to expect. As one case in point, a stress on physical traits (e.g., facial features; Borthwick, 1996) might jump-start a downward spiral of poor functioning. By pointing toward failure, doctors’ unspoken biases may disrupt natural bonding experiences between the infants and their parents—increasing mental health risk. In fact, parenting a child with a disability is linked to maternal depression while mental health benefits are associated with positive views of one’s infant who has a disability (Hollins, Woodward, & Hollins, 2010). In this setting, parents’ emotional assets are priceless.

What is the significance of this project?

Professionals have unspoken negative views of persons with disabilities (Wilson & Scior, 2014). Yet we have no data on doctors’ biases against infants at risk for disability—above all not in a mental health context. Since doctors interact with high-risk infants and their families early on, their mindsets do affect this population’s well being. To know doctors’ stance would inform prevention. For example, if doctors urged parents to help their infants be engaged, energized, and thriving per an “emotion-as-driver” model (Greenspan, Greenspan, & Lodish, 2010), infant and parent distress might be reduced. In this way, doctors could help parents strongly attach to these infants—thereby improving mental health both for the parents and the infants.

What are the goals of the project?

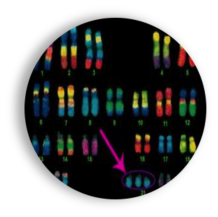

This project is an online survey of pediatricians; it will start in May 2017. It asks doctors to read stories about newborns who have one of four medical diagnoses (e.g., Trisomy 21). Doctors rate each infant’s potential for emotion-based thinking (e.g., paying attention, engaging with the world) and daily living skills (e.g., learn to read, drive a car). They also rate how likely the infant is to have mental health problems. Doctors next read about and rate the infant’s parents on varied traits plus likelihood for mental health difficulties. Finally, they complete a word-pairing test for bias against disability. Our results will help us build data about doctors’ unspoken impact into attachment-based mental health promotion models for parents and their at-risk infants.

Budget

Budget Overview:

Random national sample of licensed pediatricians. To get this random national sample, I must buy access to email addresses. The American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile will help me recruit a sufficiently large sample size—i.e., to have statistical power—to see if my study hypotheses can be supported. The AMA Physician Masterfile is a relatively economical source of physician contacts at about 40 cents per name and has the credibility of the AMA behind it.

Participant reimbursement. Response rate for physician completion of surveys is improved when reimbursement is provided (i.e., $5 cash if a mail-in survey; Amazon gift card for an online survey). In my study reimbursement will either be a small amount for each respondent ($10 or $15) or a larger amount for every nth (e.g., fifth, tenth) pediatrician who accesses the survey.

Endorsed by

Meet the Team

Affiliates

Affiliates

Robin Lynn Treptow

Ever since I watched professionals and family members mourn the birth of my son—who has a disability-related medical diagnosis—I have set my mind to rooting out the social basis for why persons with this condition (Trisomy 21) are seen as less capable than others. I even re-named the disorder’s informal name (i.e., Double Scoop vs. Down’s syndrome) because I felt so strongly that its poorer-learning outcomes resulted from widespread social rejection—which muted chances to absorb knowledge readily (see Borthwick, 1996).

I had assessed and treated very young children with special needs. I knew about “self-fulfilling prophecy” where what others (e.g., teachers) think drives how much a child learns and “learned helplessness” where no one thinks a problem can be solved so everyone gives up and no longer tries to solve it. But it was beyond my skillset to make sense of how deep the unspoken biases against a person with my son’s disorder were. As he grew, I built research skill to tease apart the question. With co-authors, I published my Experiment.com study of pediatricians’’ unspoken negative ideas about newborn infants with medical conditions expected to result in learning or other problems.

I have doctorates in clinical psychology (University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1999) and infant-toddler development (Fielding, 2019), trained on a Federal infant-toddler grant (University of Nebraska Medical Center, 1990), earned my Premedical Studies Certificate (Harvard Extension School, 2025), and am in the current medical school application cycle. I have presented on diagnosis-based bias at the World Association for Infant Mental Health (Prague: 2016; Dublin: 2023) and on racial bias at the American Psychological Association (2023, 2024, 2025). Further, I guest-presented a case study on overcoming bias in a Neurodiversity classroom at Harvard Extension School (2025), and will give a keynote for the International Conference on Pediatrics, Neonatology, and Child Health in March 2026.

Joy V. Browne

Joy Browne is an Infant Mental Health Professional and Clinical Nurse Specialist who has over 35 years experience with medically fragile babies both in hospital intensive care and as they transition to their community home. Her work has focused on supporting families in understanding and supporting their newborns and young infants, especially those who have eating, crying and sleeping problems early on. She has worked with many of these children and their families when resulting behavioral and emotional challenges become apparent and families are at a loss for how to manage their emerging mental health concerns. In her work with professionals in the community, she collected data that showed a lack of educational and assessment resources to work with these babies and their parents. So, she developed a training program that includes how best to assess and provide intervention strategies that meet the needs of this particular population. Along with the training program, Joy and her colleagues developed the Babies Adaptive Behavior Inventory (BABI) to help professionals know best how to support newborns and young infants early on. Initial validation has begun, but the next step needs financial support for the volunteers who are wilingly providing their time and energy to get the BABI birthed!

Additional Information

This project’s key goal is to look at unspoken negative attitudes towards newborns with disability-related diagnoses in the context of better mental health for those infants and their families. Although it has not yet been applied to infants and doctors, scholars today are probing unspoken bias related to disability (e.g., Enea-Drapeau, Carlier, & Huguet, 2012; Wilson & Scior, 2015).

Our study will assess pediatricians’ disability-related implicit bias and compare that data to their perceived likelihood of mental health diagnoses for these infants and their parents. Doctors’ views of parents who have differing expectations for their at-risk infant will be a factor of interest. Evidence of doctors’ bias towards newborn infants at risk for disability will help us build models of support for parents who want to keep alive their vision of the “idealized child” rather than grieve and accept a less ideal one as is often advised (Foley, 2006). This outcome is important; the stories parents tell themselves affect what they do (Lee, Park & Recchia, 2015). Negative views can feed downward developmental spirals (Cicchetti & Masten, 2010). In contrast, a positive outlook toward one’s infant with a disability may bring mental health benefits (Akram & Hollins, 2010; Hollins, Woodward, & Hollins, 2010).

For more about our team see this video at https://www.dropbox.com/s/t1r9...

For more about our team see this video at https://www.dropbox.com/s/t1r9...

For extra videoclips about this project see https://www.dropbox.com/s/r8zm...

Project Backers

- 9Backers

- 108%Funded

- $326Total Donations

- $36.22Average Donation