Please wait...

About This Project

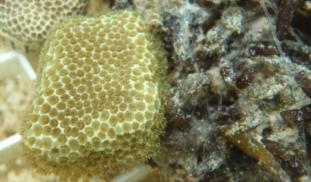

There is more algae on coral reefs than ever before and humans are to blame. Can we use next generation techniques to play "Dr. Doolittle" and find out just how the coral animals feel about living in contact with algae? We know that some algae can kill coral in the lab, but we also know that algae and coral can grow next to each other on the reef seemingly unaffected. What hidden effect is algae having on coral? How will that impact the way we survey and manage coral reefs to preserve them?

More Lab Notes From This Project

Browse Other Projects on Experiment

Related Projects

Out for blood: Hemoparasites in white-tailed deer from the Shenandoah Valley in Northern Virginia

Our research question centers about the prevalence and diversity of hemoparasites that infect ungulate poplulations...

Using eDNA to examine protected California species in streams at Hastings Reserve

Hastings Reserve is home to three streams that provide critical habitat for sensitive native species. Through...

How do polar bears stay healthy on the world's worst diet?

Polar bears survive almost entirely on seal fat. Yet unlike humans who eat high-fat diets, polar bears never...